Map size in jpg-format: 30.3953MiB

Click to open in high resolution (open in new tab).

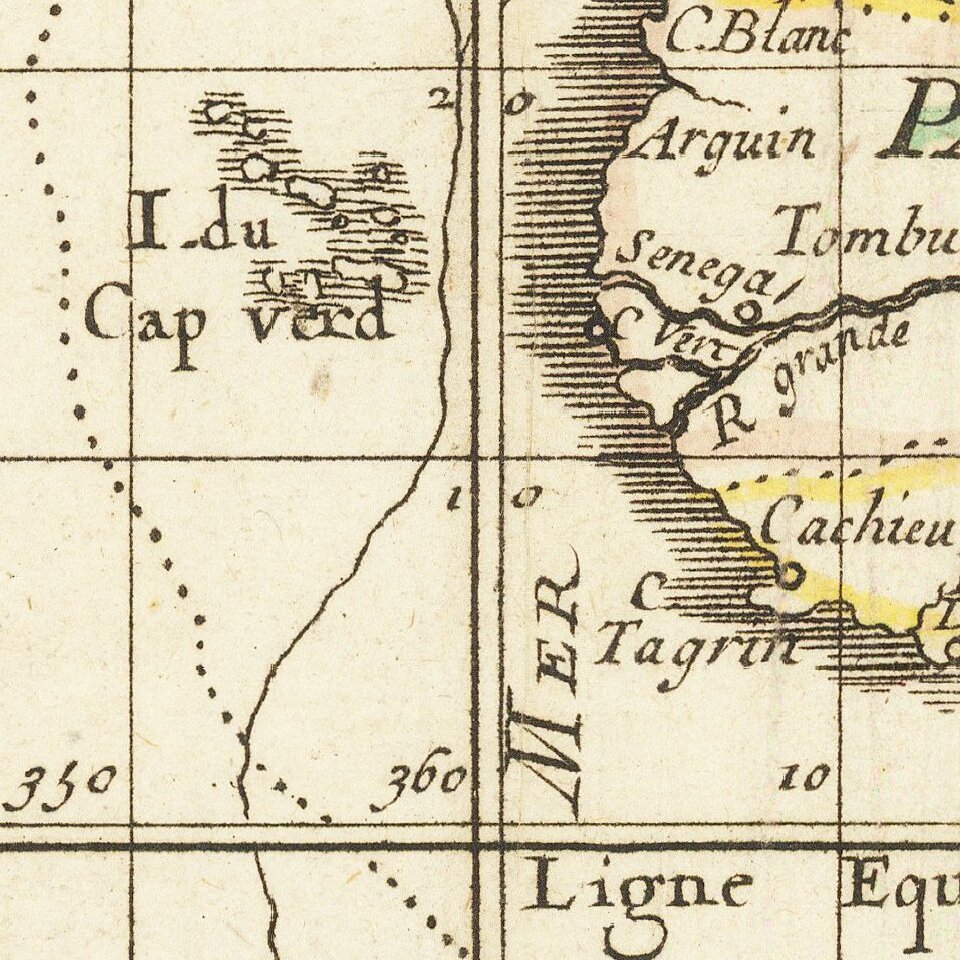

Illustrating the Major Commercial Sea Routes of the 17th Century

First state of Pierre Du Val's scarce 17th Century map of the World, illustrating the most important world trade routes during the middle of the 17th Century.

Du Val's map is constructed on a plane projection and illustrates the scientific approach to cartography then being championed by the French, free of the embellishments then in favor in the Netherlands. The map shows the World as known in the middle of the 17th Century, including many of the great cartographic myths of the period, including

The map identifies the routes to and from the "Indies Occidentales" and "Indes Orientales", with small sailing ships shown on each route. As noted by Shirley, the routes illustrated are those used by French and English ships, rather than the more southerly routes across the Indian Ocean, and then to the north, preferred by the Dutch.

Du Val's map is perhaps most noteworthy for its fascinating depiction of "Terres Ant-Arctiques dites Australes et Magellaniques et Inconnues" retaining much of the mythical information that was more common on 16th Century maps, including places popularized by Marco Polo, such as the Kingdoms of Psitac (short for Psitacorum, the Land of Parrots), Beach, Lucac and Maletur (the Kingdom of Malaiur or Malays, which was placed by Marco Polo at the Southeast end of the Malay Peninsula).

Marked on the outlines of New Holland are the names of the coasts discovered by the Dutch. Du Val was at the time one of the proponents of a pre-1606 discovery of Australia by the French. On one of his other world maps of the period, he adds the following annotation on the incomplete Australian Continent: "ou l'an 1504 aborda Ie nomme GonneviIle qui en ramen a en Normandie Essonier [sic], fils du Roy d'Arosca' (where in the year 1504 landed Gonneville who brought back from there Essonier, son of King Arosca). While not specifically mentioned Gonneville, Du Val's map seems to have been influenced by the then current story of the French discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere by an explorer named Gonneville in 1504. The French explorer Captain Binot Paulmyer de Gonneville claimed to have discovered the southern continent in 1504. As noted by Howard Fry in Alexander Dalrymple and the Expansion of British Trade,

Gonneville had left Normandy in command of the Espoir in 1503, and after visiting the Canaries and Cape Verde, he had apparently crossed the Equator on a south-southwesterly heading, until he had been driven off course by a violent gale when in the latitude of the Cape of Good Hope. In January, 1504, he had then sighted land, where for the following six months he and his crew had lived on friendly terms with the natives, one of whom accompanied them on their return voyage. This was Esomeric, the son of a local ruler. Back in the English Channel, the Frenchmen had been attacked by an English pirate, and had lost their ship and papers. Many of the crew, however, survived, including Esomeric, and in an effort to get redress from the English, Gonneville made a statement to the naval authorities, an authenticated copy of which survived. The memory of this voyage remained alive, but the document gave no clue as to where this discovery was to be placed, and later interpretations were to include South America, Madagascar and even Australasia, to the south of the Moluccas.

Du Val was then serving as Royal Geographer to the King of France and his maps were of great commercial and geopolitical importance.

The map is rare on the market, especially in the first state. Later editions appeared in 1677 and 1686, with revised dates on the map.

If you are a student, write to us in telegram: @antiquemaps and indicate what material you need and for what work you need a map in high detail. We are ready to provide material on special terms. For students only!